How We Carved Imagination Out Of Learning

The Stopwatch Experiment

- Start a stopwatch and tell a child:

“The universe is made of atoms. Atoms are the smallest units of matter. They connect to other atoms to form everything around us…”

Try your best. Use a colorful voice. Be enthusiastic. Add gestures. Make it dramatic.

Stop the watch when their eyes begin to drift.

Ten seconds? Thirty? A minute, if you really bring the drama.

But almost inevitably, their attention will wander.

- Now reset the stopwatch and say:

“Once upon a time, there was a tiny kingdom. And in that kingdom lived a king with the strongest power in the universe…”

Stop the watch when the child loses interest.

You will probably have to finish the story (and three more for that matter) before you lose the child’s attention.

In fact, unless you actively try to make the story boring, by mumbling, rushing, or draining it of all emotion, it will still take effort to make them disengage.

Why?

You probably think: “Well of course it makes sense. Stories are fun…”

… But?

What isn’t fun?

Textbooks?

Atoms?

Science?

Learning?

Everyone says that learning is fun, so why do kids refuse to listen?

Why can’t they focus on our abstract factual ideas, and have fun?

Surely if we push harder, with more tests, more pressure, more punishment, or dangling carrots, they would finally feel the fun.

Would they?

The Fire Experiment

Let’s take a look at how the human mind is built from our very beginning.

Tell a toddler that fire is hot.

Put in your best effort, bring your strongest arguments, your most precise thermometers, the best papers that prove it, and explain to them logically that they should never touch it because they’ll get burned.

At best, they will look at you and smile.

Because a toddler needs to experience heat to understand that fire is hot.

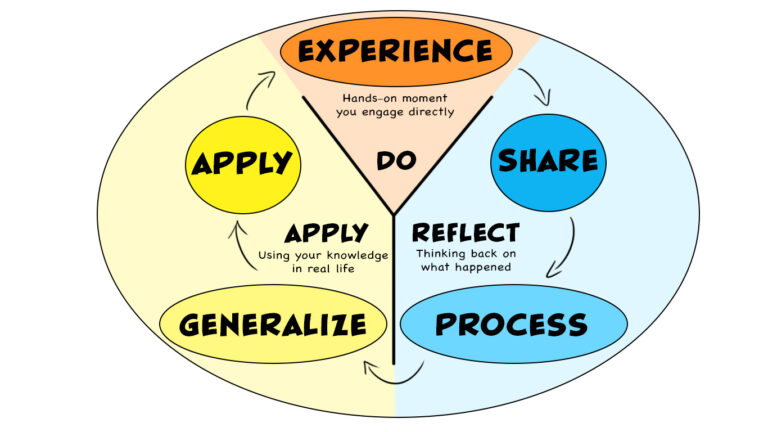

John Dewey described this as “experiential learning”. A cycle of experience, reflection, and application. In other words, we don’t learn by being told.

We learn by living.

John Dewey’s cycle of learning: From real-world experience, not abstract instructions.

Lists of facts and abstract arguments are an adult invention. Adults are trained (slowly and painfully) to sit still, and to abstract, memorize, and operate symbols detached from life.

Children are still much closer to the “primal” human mind: the part that learns through experience, emotion, imitation, and imagination.

But imagination is not just for children.

Imagination is our greatest cognitive tool.

As Christopher Booker argues in The Seven Basic Plots, what truly separates humans from animals is not just intelligence, but our ability to imagine ourselves in situations we have never lived through and/or never will.

Imagination helps us simulate futures or alternate realities, rehearse dangers, explore possibilities, and learn without paying the full price of reality.

The Imagination Experiment

Now do this yourself: Close your eyes and think of an atom.

Did you picture something in your head?

What was it?

Little connected balls?

Little people?

A tiny solar system?

Whatever your picture was, it was your personal translation of the word: Atom.

At some point, somewhere, someone explained to you what an atom is. What you did was to translate and connect it to an image that you are familiar with. First to understand it, second to remember it.

As Pablos Holman explains in Deep Future, this mental model you built without any effort is essentially a simulation in your head, and that simulation (even wildly inaccurate) is sufficient for you to understand everything around you.

Now do the same with the word: Freedom, Justice, Time, Sharp.

We use our imagination to connect abstract meanings to very concrete and familiar images.

Even the most rigorous sciences are built on metaphors and mental images:

The electric current flows.

The genetic code is read and copied.

The heart is a pump.

The fabric of space and time.

Why?

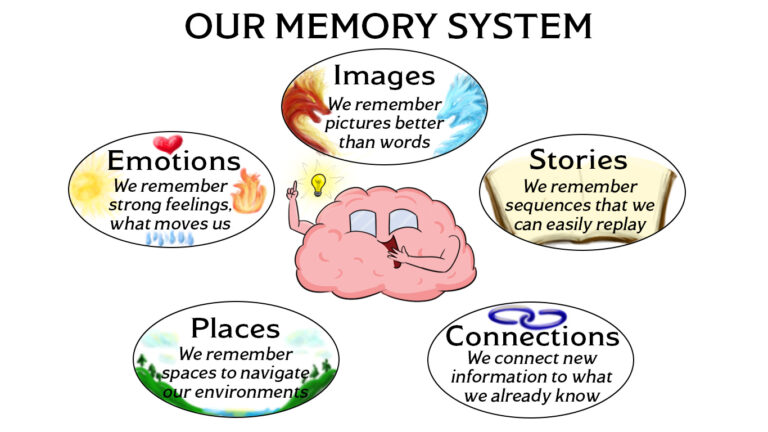

Joshua Foer, in his book Moonwalking with Einstein, noticed that memory champions don’t remember numbers or cards. They remember emotional images and stories. They translate cold data to absurd, vivid, emotional scenes, characters, and journeys.

The brain is not a storage device.

The brain is a meaning-making machine.

By using the brain’s natural strengths, you can remember anything, no matter how complicated and data driven it is.

How Humanity Learned Before Schools

Humans were able to transfer vast amounts of knowledge across generations long before the written word.

How?

Consider where you first heard about good and evil.

Most likely in one of the most influential texts in human history: The Bible.

Following religion or not, you have to admit that there’s something extremely extraordinary about this text. It is one of the most refined, interpreted, argued over, retold, and long-lasting stories ever told. It has stayed alive for thousands of years and, in large parts, it shaped Western civilization.

Now consider the Epic of Gilgamesh, Beowulf, the Greek and Norse Myths, and even the Little Red Riding Hood.

These were not told as “entertainment”.

This was compressed knowledge about danger, cooperation, courage, protection, betrayal, responsibility, and what kind of people we should be.

Little Red Riding Hood might sound like a story about a girl and a wolf, but in reality it’s a warning about trust, naivety, and predation on the weak and inexperienced.

Beowulf might sound like a story about a hero and a monster, but in reality it’s about the expectations society has of its strongest members in times of existential danger.

The point was to translate knowledge into absurd, vivid, emotional images so mankind would survive.

The same principle applied to practical knowledge too.

Metaphors are one of the best ways to pass knowledge on.

When you want to teach someone how to do something, you won’t give them abstract instructions, will you?

You will use words like:

Make it sharp like…

Make it strong like…

Look for the fruit that looks like…

In other words human knowledge did not grow through definitions, but through shared imagination.

History Is Our Story

In Greek the word ‘story’ and ‘history’ are one and the same: Historia (Ιστορία).

Conceptually, it’s true. We don’t really understand the past as a list of events. But we do understand human journeys: struggles, failures, discoveries, courage, mistakes, and redemption.

That’s why when you hear Einstein’s personal story, you immediately care more about what he discovered. We always connect more deeply to achievements when we know the human story behind them, whether it’s a scientist, an innovator, an actor, an author, or even a dog, or a cloud.

Because story is the compressed human experience.

The Day Stories Disappeared

After centuries of using stories as our main vehicle for knowledge, one day we banished them to the “entertainment” section.

We deemed the natural way of understanding the world somewhat… unprofessional, and spent enormous resources building a system designed to separate imagination from learning.

Stories are just for literature.

Imagination is just for art.

And play is just for recess.

Real learning is supposed to be: abstract, serious, detached.

But when they teach you the word atom, you do imagine a familiar mental picture to connect it to the word.

Don’t you?

Don’t they?

Yes, everyone does, but now it needs to be a secret.

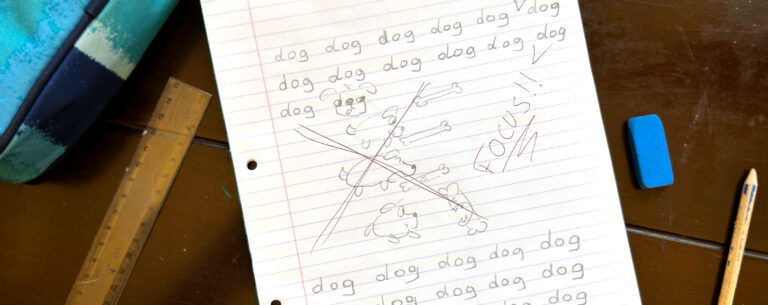

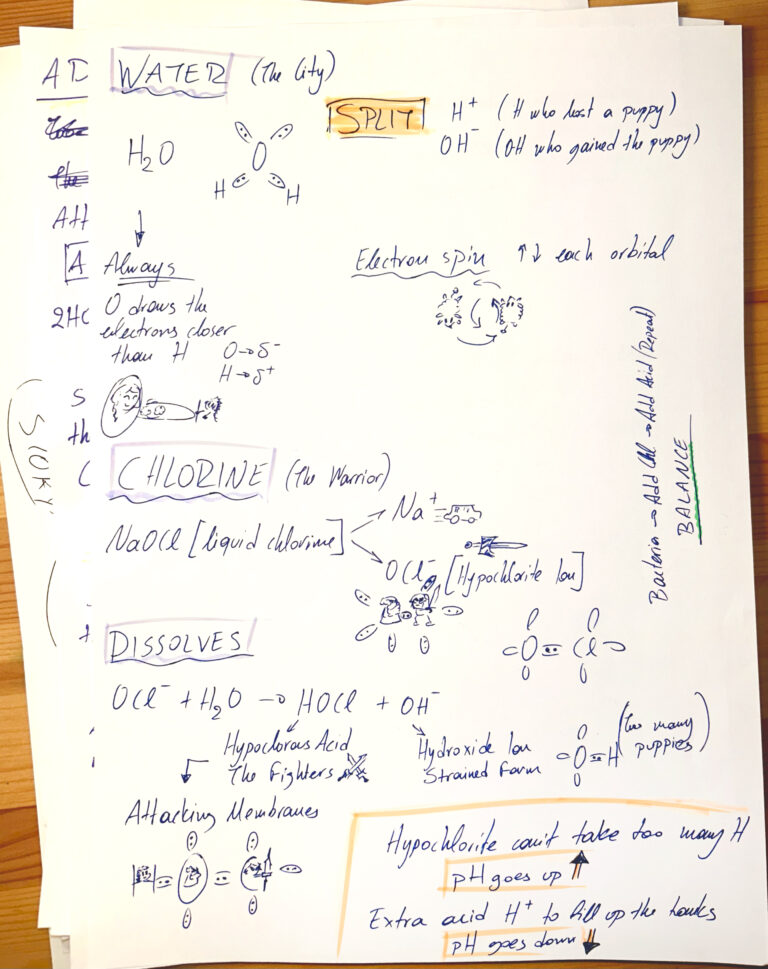

I was a straight-A student and it took me years to realize that when I was reading the textbooks, the only way to understand and remember those nonsensical theories, was to take a piece of paper and redraw everything using my own images.

When I finished my studies, I had entire textbooks, retold and rewritten, to absurd, vivid, emotional scenes, characters, and journeys.

When one of my teachers happened to see that, I was scolded and made an example of:

Imagination has no place in class.

So I kept it a secret. A shameful but very real secret.

I still write notes like this today, when I research/refresh topics for my next stories.

The Serious Work of Play

Peter Gray, in his book Free to Learn, pointed out that children learn best through play.

When children play, they explore danger, rules, morality, and consequences in a safe simulated world. They essentially live and learn without paying the real price.

And interestingly, when adults want to get creative, they enter a state of play.

Reframing a problem as a game, a space of possibilities, it becomes alive and the mind does what it does best:

It uses imagination.

My First Story Experiment

A few years back, my son fell on the playground and was inconsolable. Seeing the blood running from his cut, made him really scared and he couldn’t connect back to logic, no matter what I tried.

Textbooks, facts, my strongest arguments, my most precise thermometers, and the best papers on the topic, did not help either.

So I tried what our ancestors did for centuries:

I told him a story.

Only it wasn’t meant to entertain him, nor distract him. I wanted to make him understand what’s happening.

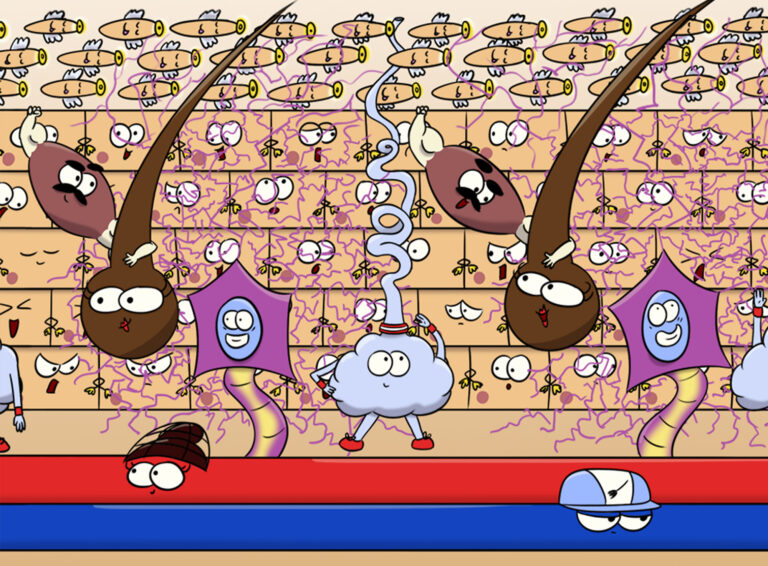

I created a vivid and absurd image of his skin cells and organs, how they suddenly had a world-breaking event on their hands, and how they would have to work together now to avoid absolute catastrophe.

I built him a story that literally sprang out of science.

To my surprise, not only did this calm him down, but I caught him later explaining it with extraordinary detail to his brothers and friends.

Each organ didn’t just have a function, it had a character, a background, aspirations, and goals. They had to work through all that to find a way to save him.

The Hidden Story Inside Everything

I didn’t invent a story at that moment. I knew the theory and I translated it to a vivid mental image.

Atoms can be little balls, but they can also be kingdoms that seek to form alliances.

Cells can be close-woven societies that vow to protect at all costs.

And water molecules can be the backbone of a great civilization.

Every subject hides a story in it.

A story that will make it understood, learned, and remembered.

A story that will bring it to life.

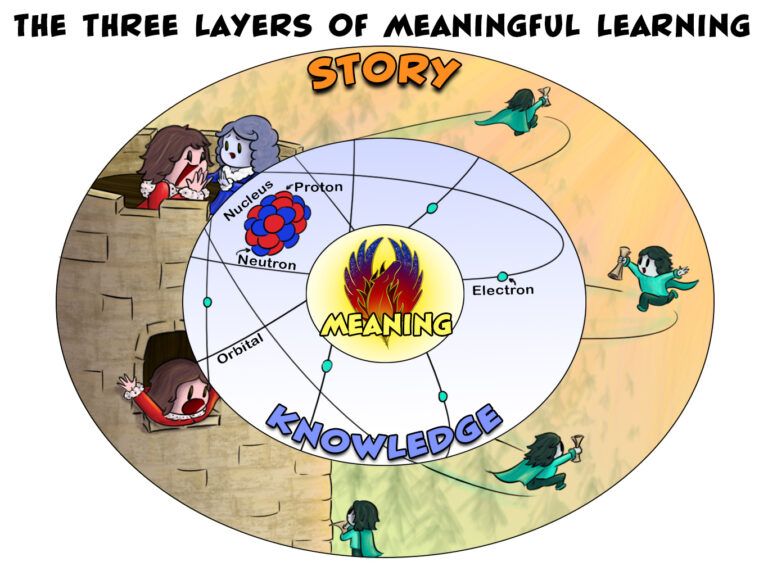

The Three Layers of Learning

What it means for me to reintroduce imagination into knowledge.

The three layers:

- The story itself.

This is the mental image, the metaphor created from translating the knowledge. The narrative that the human mind understands.

But it has to be a real story: with characters, goals, tension, stakes, arcs, change, a beginning and an end.Example of a story-based set-up: The atom is not protons, neutrons, and electrons.

An atom is a tiny kingdom. In the center, in an (almost) unbreakable castle, live the noble Protons, who have only one crazy positive dream, to expand their kingdom, and their Neutron wives, who keep the Protons’ meetings neutral (before they break the entire castle with their uncontrollable positivity).

Protons are certain that with bigger kingdoms, they will be able to create new, unimaginable things, and they do have a secret weapon: Their faithful little ambassadors, the Electrons. They always zoom around looking for new kingdoms, and when they find a fitting one, their negativity works as an excellent negotiation tool to form strong alliances. - The knowledge.

This is the real science. Nothing is moved, ignored, or diluted. It is woven inside the story, translated from abstract to tangible and familiar.

Kingdoms, noble families, ambassadors, and land expansion are much closer terms to a child’s reality than protons, neutrons and electrons. But reading about them, they are actually learning about the abstract, in a way that will make sense for them.

The knowledge can be anything, from physics, chemistry, biology, engineering, and medicine, to psychology, gardening, or woodworking. - The meaning.

This is what humanity made stories for. To teach about deeper abstract meaning, and give future generations a guide for successful living.

Cooperation, fragility, balance, growth, responsibility.

This is the layer that is absorbed without lectures or moralizing. Without explanation.

This is our duty as storytellers to give the right tools to humanity.

Each subject has to exist in all three layers, and they have to work together flawlessly, and without being noticed.

When meaning, knowledge, and story align, learning stops being work and becomes an experience.

The Deeper Goal

The goal in education should not be to simply teach about atoms.

Our ultimate goal should be to restore the love of learning that kids are naturally born with.

All babies are naturally drawn to novelty.

Everything new, they have to touch it, smell it, turn it around, explore it (or even lick it). They immerse themselves so much into the experience, they lose every other sense and of what’s happening around them.

And this focused curiosity is not witnessed only in children.

That’s the natural human state of learning.

How many times did you immerse yourself in something new, and suddenly it’s dark out?

But there comes school and redefines learning as an effort. Pressure, tests, work, stress, memorization, obligation, boredom.

With a story-based, imagination-powered approach, knowledge feels like discovery and exploration again. Learning becomes exciting and empowering.

It stops being the annoying thing you have to do, and becomes the fun thing you get to do.

Math Is Not A Subject

“Math is too abstract for stories. Math by definition has to be abstract.”

Does it?

Let’s take a step back and think what math is.

Right now, math is another subject you study, but that’s completely backwards. By reducing math to a subject like chemistry, we stripped it from its reason for existence.

It lost its meaning.

Math is not a subject.

Math is a language!

We didn’t invent it because we love symbols.

We invented it to describe, understand, and communicate the world around us.

Teaching math just for the sake of it, is like teaching grammar and never writing a story, or teaching vocabulary and never using it to speak. Some people like it, they find beauty in the abstraction of a language. I’m one of them. I love math for its own sake.

But no-one can deny that this is the exception and not the norm.

So the question becomes simpler:

Not if you can teach math with stories,

But how can we teach math without them?

Math Is A Language

When my own children came from school confused about the “rules” of math, I tried to explain. Soon enough, they flooded me with questions: Why does this come before that? Why that first? Where does this go? How will I ever remember all that?

We were looking at procedures and rules that made no sense to them, and frankly they couldn’t care less.

But what happened when stories were involved?

Through Minecraft, Warcraft, Asterix, and Harry Potter, instead of trying to memorize multiplication tables, they had to figure out how Arthas, the fallen prince, could raise 10,000 undead soldiers by using 50 mages with 10 shadow runes each, before he arrives at the High Elf city of Silvermoon, if he travels at 20 kilometers every hour.

Suddenly, multiplication, division, addition, subtraction were not just operations.

They are decisions inside a story.

The story provided the logic.

The math became the tool.

And nothing had to be memorized anymore.

It made sense.

Because in real life, most of them will never have to solve for x.

But they will have to calculate recipes, plan distances, manage resources, estimate time, and divide responsibilities.

Math becomes meaningful when it returns to the world it was created to serve.

The Homework Experiment

One afternoon, we were drowning in homework. The phone kept ringing with messages from the teachers that if they don’t complete their homework this time, they will have to take their recess away.

On a table full of papers, pressure, stress, screams, and tears, I had to convince my children that learning is fun.

I felt my blood pressure rising and my heart about to jump out of my chest. I knew that if this continued, I will destroy myself and them.

So I leaned back and asked myself why?

Why are we spending our precious time together like this?

Is this learning?

If they complete enough worksheets, will they eventually learn to love math?

Would that make them geniuses, confident, curious, successful, happy?

When they were babies, I never forced them to crawl, to walk, to smile. I never had to sit them down to “practice” curiosity.

They did it because they wanted to. Because it’s their natural state.

And when they wanted it, failure didn’t matter.

Failure wasn’t even in their vocabulary. They would try in endless loops until they succeeded and moved on.

When I wanted to write and illustrate my first book, I knew nothing about it.

But I wanted to.

I sat on it for endless hours, not because someone was watching nor because I was obligated to.

Was it hard? Immensely.

But failure had no place. Only curiosity.

Your kids, my kids, spend hours building enormous, mind-numbingly complex worlds in Minecraft. Block by block, for hours and days.

Or study every little detail of every little movement from a dance they saw and want to replicate.

Or read Harry Potter again and again and again until they memorized it better than every book humanity ever read.

Why?

Not because school told them they have to.

Because they chose to.

Is it hard? You bet it is.

But fear of failure is absent.

Curiosity and imagination are in the front seat.

That is what learning looks like when it’s alive.

We don’t have to invent new, better ways for children to learn.We need to remember the oldest, strongest, most effective one.

The one we already have.

Knowledge didn’t change, except the way it was told. Suddenly, it makes sense.